Students always ask me the best way to develop speed. I believe this article from my SiGung’s website provides a good starting point on this subject. Enjoy!

SiFu James Sasitorn

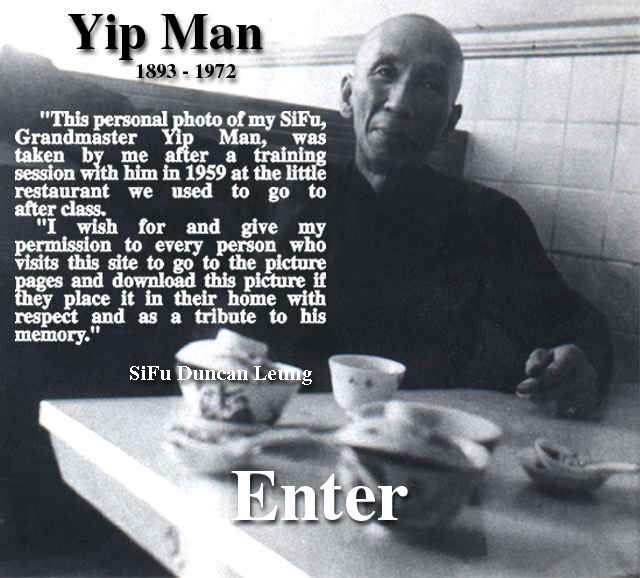

What Yip Man Taught Me About Speed by SiFu Duncan Leung

Originally Posted: http://members.tripod.com/wing_chun/hpageie.html

Recently an acquaintance gave me a copy of QiGong/KungFu Magazine, the March 1999 issue, which featured an article written by Master Ron Heimberger. My friend did not quite understand the principles that Master Heimberger was trying to elucidate. Because of my background as a private student of Yip Man, and my subsequent involvement in Wing Chun Kung Fu, he thought I might be able to throw some light on the subject. I ask the reader’s indulgence for my attempt to explain what Yip Man taught me.

Since my English is not very good, I read the article several times. I am glad that Master Heimberger is kind enough to take the time to educate the public. If all Wing Chun instructors possessed an open mind like him, amenable to reason, and were willing to go to the trouble of explaining their ideas and experiences to others, I am sure it would benefit everyone interested in the art. However, there are some parts in Master Heimberger’s article with which I do not agree. Certain points that the author makes are somewhat obscure to me, particularly his references to Jacob Bronowski and Albert Einstein. For example, Master Heimberger mentions that Bronowski — commenting on Newton’s Second Law of Motion — said that force equals mass times acceleration squared. This confuses me because, as I understand it, Newton’s Second Law states that S F = ma, which does not square acceleration.

Since Mr. Heimberger discusses speed in Wing Chun, I would like to take the liberty to share my interpretation of the principles and theories about speed based on what SiFu Yip Man taught me and on my own experience. Naturally, what I write here is filtered through my own perceptions and prejudices; I certainly do not claim to speak for the Wing Chun family, and would welcome any correction that is offered. That certainly would help me improve. It is my hope that many Wing Chun members will share their ideas with all of us, no matter who they have learned from. The experience of using the Wing Chun techniques in fighting is what counts. After all, no single fight is the same. We can always learn something new, or — win or lose — find out something from each encounter.

What makes the Wing Chun style so interesting is that one does not have to rely on physical build, but on a logical sequence of economic movements. Certainly speed is extremely important in fighting. However, no matter how hard one trains, how long one works to improve, there are always physical limitations. You can always meet someone faster than you. Some people are simply born with more talent. Wing Chun allows one the possibility of overcoming an opponent’s inherent superior speed by applying the principles of the art. Yip Man taught that in Wing Chun, there are several types of speed. If you cannot overcome your opponent with one type of speed, you can beat him with another. In other words, if you can apply the Wing Chun theory of speed, you can actually become faster. In this regard, there are four areas of concern:

1. SPEED OF TRAVELING: This is the type of speed we normally refer to, that is, a punch or kick, a speed which speed can be calculated in feet per second. With consistent practice, one gradually improves the speed of the movement.

2. SPEED OF DISTANCE: Wing Chun straight-line theory states simply that a straight line between two points is the shortest distance. Therefore, punching straight is shorter and quicker than a hook punch or a swing. To bring your foot with a roundhouse kick to the head covers a greater distance than a shorter and quicker punch to the head. It is the same as trying to punch to the shin; that is, it is much shorter and faster to kick to the shin. To use an analogy: if you and I both stand in front of a building and have a race to the back door and you go around the building while I go straight through the building from the front door to the back door, you may be the faster runner, but I may get there before you because I have less distance to cover.

3. SPEED OF READINESS: From a resting standing position, when one tries to throw a heavy punch or tries to kick with power, it is typical to cock back the leg or arm before executing the movement. This not only telegraphs the move, but also wastes valuable time in the extra motion. In Wing Chun, the power is not generated just by the moving hand or leg, so there is no need to cock. One uses the other side of the body to pull back as he or she rotates to push out the punch or kick simultaneously. For example, if one is going to throw a left punch, one initiates power by pulling the right arm and shoulder back as fast as he or she can, while punching with the left hand at the same time.

4. SPEED OF REACTION: In general, people spend most of their time practicing their techniques in their forms alone until they are very good with all the techniques, but in actual combat the application is ineffective. This is like learning to ride a bicycle by sitting in a chair moving the legs and arms simulating the bicycle experience. When that person actually tries to ride on the bicycle, he or she will surely fall. This is because the proper reflexes and feeling of balance have not been developed. Yip Man used to say if you want to learn to swim, go down to the water; don’t just move your arms and legs and think that you are a swimmer. A fight requires at least two people. You can train and fight with yourself all day long, but unless you apply the techniques with another person, you will not get very far.

Wing Chun has only three forms. After learning and understanding the first form, one trains with Chi Sau, which requires two people, and from which one develops the feeling of contact and reflex. Then there are the technique drills which also takes two people. When you work with the drills over and over, month in and month out, they become habit, second nature. When an attack comes you will react to it without thinking. Fighting happens so very fast and you may be upset, angry, unprepared or even scared. There is no time to think.

Such are the Wing Chun Theories of Speed that I learned from Yip Man.

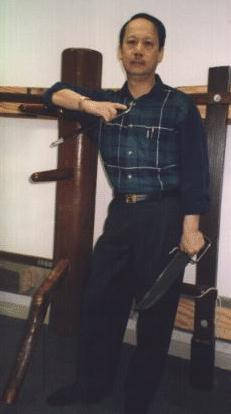

SiFu Duncan Leung